Idempotence is a topic that can be both simple and hard. Here, we start from simple with a trivial use case in a single-state application. Then we’ll go deep, to discuss the most complicated use case for building a highly reliable system with multiple states.

What’s Idempotence

Let’s start from Wikipedia:

“Idempotence is the property of certain operations in mathematics and computer science whereby they can be applied multiple times without changing the result beyond the initial application.”

But what does it really mean by “not changing the result”? I see two ways that we interpret it:

- No matter how many times I made the same request, I will always receive the same response.

- No matter how many times I made the same request, I won’t change the state of the system.

The two statements sound similar and both seem to be correct from the surface. However, the second statement is more appropriate. We’ll discuss this further in the following sections.

Idempotence in a Single-State System

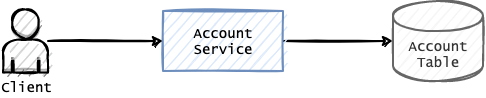

Let’s consider a very simple system with a single running service on top of a single database.

Image credit: Author

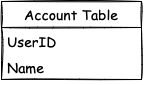

The database keeps track of user accounts. Each account simply has two properties: UserID and Name.

And let’s assume the service provides four basic CRUD operations (CREATE, READ, UPDATE, and DELETE).

These APIs are defined as the following:

createUser(userId, name)

readUser(userId) -> User

updateUser(userId, name)

deleteUser(userId)

Let’s take the READ operation as an example. It is commonly agreed that READ is idempotent.

However, if we make a READ request, and encounter a network error (i.e., timeout), and retry, we won’t necessarily get the same response as the initial request. Why?

Because some other actor of the system might have changed the state of the system. For example, updateUser might have been called between the first and second READ.

For the CREATE operation, if we get a network error during the createUser request, then the state of the system becomes non-deterministic, just like Schrödinger’s cat.

If the record has not been created, then the retry will trigger the normal insertion into the database.

If the record has already been created, that’s when things get interesting. What should we respond to the client? Consider the following two options:

Error: Your record {userId: 'yuchen123', name: 'Yuchen'} already existSuccess: Your record {userId: 'yuchen123', name: 'Yuchen'} is created

Both options are valid. From the client’s point of view, returning the same response may be more user-friendly since the client only cares about the result of the CREATE operation.

However, on the other hand, we could also argue that a different response provides more transparency, making it clear that the previous request was successful. Let’s assume that we’ll go with option one for now.

A Case With Two Clients

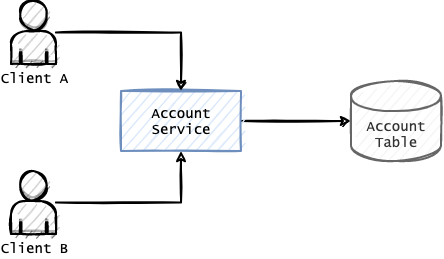

If we have two clients, and both of them are making the same request to create a user:

createUser(userId: 'yuchen123', name: 'Yuchen')

Assuming the network was not stable, both of the requests from client A and client B successfully reached the server. However, neither of them receive a response.

Image credit: Author

A bit later, both of the clients retry and both of them receive an error message:

Error: Your record {userId: 'yuchen123', name: 'Yuchen'} already exist

Interestingly, with the current setup, there is no way for us to know which of the two client’s initial requests was successful.

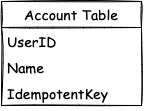

One common approach is to introduce an idempotentKey. It is also sometimes referred to as idempotentToken, requestId, nonceToken, etc.

Now let’s change the create request to the following:

createUser(userId, name, idempotentKey)

And the requests from Client A and Client B can now be different.

From Client A:

createUser(

userId: 'yuchen123',

name: 'Yuchen',

idempotentKey: 'a2906959'

)

From Client B:

createUser(

userId: 'yuchen123',

name: 'Yuchen',

idempotentKey: 'b54ed6d9'

)

From the server-side, when inserting this record into the database, we also include the new column idempotentKey.

When a client retries, it will use the same idempotentKey from its previous request. With this, we can then identify which client’s request was successful earlier.

For example, if we see a record with idempotentKey being a2906959 in the database, we can then return the following to the two clients.

Response to Client A: Success: Your record {userId: 'yuchen123', name: 'Yuchen'} is created.

Response to Client B: Error: Your record {userId: 'yuchen123', name: 'Yuchen'} already exist.

Notice that we are using short strings as the idempotentKey. In practice, they can be anything as long as they are unique.

A Dilemma Between At-Most-Once vs. At-Least-Once

Large scale distributed system is unreliable and unpredictable by the nature. A server can crash at any given point in time.

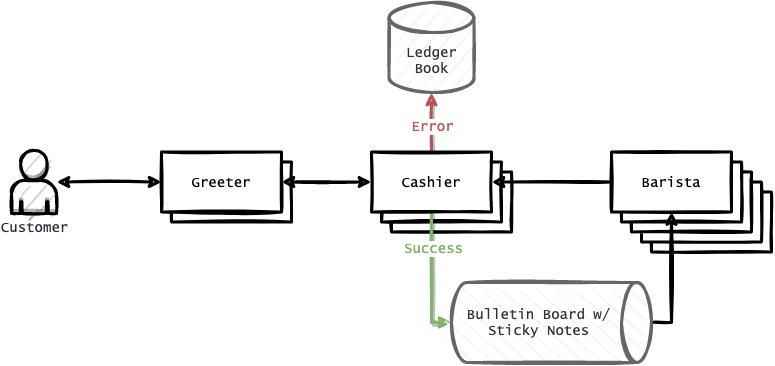

A while ago, I described a system for ordering coffee in the blog post System Design in Layman’s Terms. Over there I wrote:

… the cashiers write down the transactions in the ledger book at the same time as they put the sticky notes on the bulletin board.*

But I didn’t explain how they can do that at the same time. What happens if the cashier writes down the order on a sticker note for the barista, gets distracted by a phone call, and then forgets to write down the transaction on the ledger book afterward?

A situation like this is widely discussed in distributed message queues. When we have a new message from the message queue, should we:

- first, acknowledge that we received the message and then process it

- process the message first and only acknowledge the message once the processing is complete

Choosing between (1) and (2) will result in at-most-once and at-least-once delivery respectfully.

One solution is with atomic commit protocol, which is discussed in detail in the book “Designing Data-Intensive Applications: The Big Ideas Behind Reliable, Scalable, and Maintainable Systems” by Martin Kleppmann:

“If either the message delivery or the database transaction fails, both are aborted, and so the message broker may safely redeliver the message later. Thus, by atomically committing the message and the side effects of its processing, we can ensure that the message is effectively processed exactly once, even if it required a few retries before it succeeded. The abort discards any side effects of the partially completed transaction.”

Even though this sounds elegant on paper, it is extremely hard to achieve in practice. In the next section, we’ll look into a different way to approach this problem — with idempotence.

Idempotence in a Multi-State System

A complex system can consist of many components. But conceptually, they can be put into two categories:

- States

- Computations

A computation is what will change the state of an object. It is a small unit of executable function and is often also referred to as a step or a task.

If we focus on the states, such a complex system is sometimes called a State Machine. If we focus on the computations, it is sometimes called a workflow. Academically, this is also known as the Saga Design Pattern.

Since the system can crash at any given point in time, to make the system highly reliable, the trick is to make every computation idempotent so that we can retry them in case of failures.

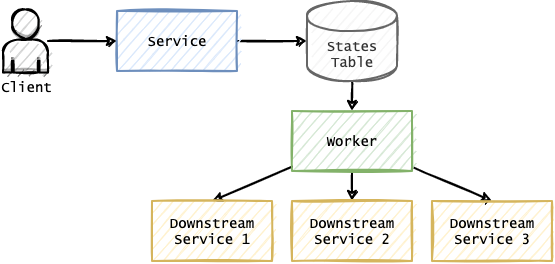

The way to enable idempotent is no different than what we’ve discussed above in a single-state system — by adding an idempotentKey to the request. On the server side, we put the request into the

database and respond to the client immediately with an acknowledgment

that the request is received. Any subsequent retry requests will be

ignored since a request with this idempotentKey is already present in our system.

It is important to point out that this system is asynchronous. We have a separate worker that will fulfill the request.

A system like this becomes highly reliable. The worker can crash at any time, and it would be fine.

For example, in an e-commerce app, the worker crashes when processing the user’s credit card. We are supposed to change the state of the transaction from “Pending Charge” to “Charged.” Since the worker dies, we don’t know if we’ve changed the user’s credit card successfully. What do we do? We simply try to charge the user’s credit card again once the worker is restarted. We are confident that we won’t deduct the amount twice as long as the request is idempotent.

From the client’s point of view, it can poll for the results. Alternatively, it can also rely on some separate systems to get notified once the request is fulfilled (i.e., email, push notifications, distributed message queues, etc.).

In short, in complex systems with multiple states and computations, the trick to make them highly reliable is to make the requests idempotent.

Where Idempotence Is Important

With such a huge benefit on reliability, why don’t we make all requests idempotent?

Some requests can obviously benefit from idempotence. For example, credit card transactions as we mentioned above. As a matter of fact, most (if not all) payment infrastructures support idempotence, such as payment APIs from Stripe or Square.

But idempotence is also expensive. It is more complicated to implement and it also has additional latency implications. Therefore, some services may not make sense to be idempotent. For example,

- We don’t need idempotency in a logging system. If the system is restarted, it is acceptable to have duplicated log messages.

- We don’t want idempotency in streaming applications such as VoIP calls, or collaborative editing tools (such as GDoc). In these systems, we prioritize availability over consistency.

As Thomas Sowell once said:

“There are no solutions. There are only trade-offs. And you try to get the best trade-off you can get. That’s all you can hope for.”

He was speaking in the context of economics. But the same can apply to us engineers as well. We need to decide which operations are critical, and we need to make idempotent, which are less critical and good enough with either at-least-once or at-most-once.

The End

That’s it for today. That was not an easy topic to write. If you have made this far, hope that you, too, enjoy the beauty of idempotence. As always, thanks a lot for reading. Do you have to use idempotence in your work? What is it that you are building? What do you find most challenging while implementing that? I would love to hear from you too!

This article is also available at https://betterprogramming.pub/1a39393df7e6.